The goal of this project is to make a method of manufacturing reusable inserts for airway epithelial cell cultures.

Background

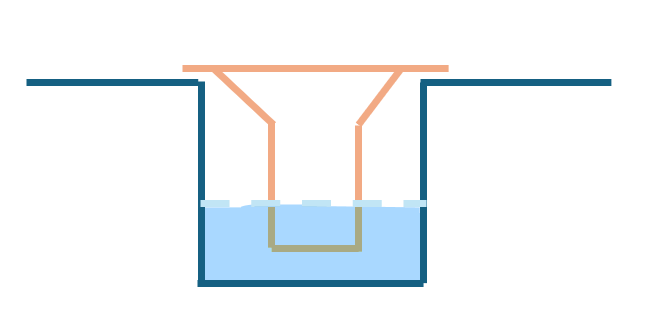

Air-liquid interface systems are often used to culture airway epithelial cells for various types of research, such as respiratory research. This is where an insert holds the membrane suspended in the well rather than flush with the bottom (as seen in figure 1). Traditional Transwell-style inserts are effective but are often expensive, single-use, and not easily customizable. In order to test the membranes, the lower half often needs to be snapped off, breaking the insert. To address this, I began developing a low-cost, reusable, 3D-printed cell culture using FDM.

Considerations

- Cost-efficiency

- Heat resistance (autoclavable)

- Modularity

- Customizability

- Easily manufactured

- Chemically resistant

Approach

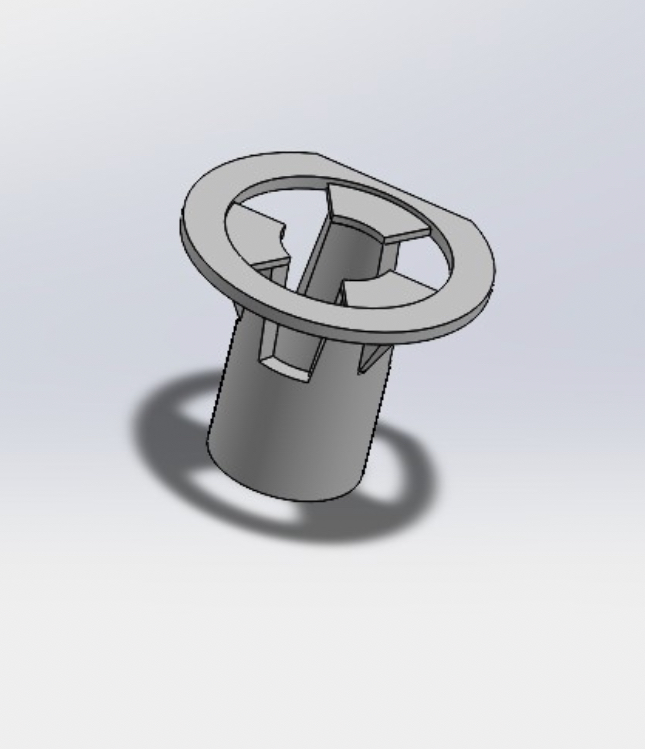

For this project I first began by creating exact replicates of the existing insert frame design. This was done with PLA (shown in figure 1). The PLA was later switched out for polycarbonate due to PLAs weak heat resistance. Polycarbonate is able to withstand much more heat than PLA, making it more suitable for a part that will go through autoclaving. After making exact replicates, I focused on making the design modular/detachable. In order to conduct testing, the bottom half of the insert is snapped off from the top half. To address this, I made the insert into two pieces, a top male part and a bottom female part. The two parts were designed with a slight clearance that allows for a friction fit. Next, membrane attachment became the main focus of the project.

Membrane Attachment

After replicating the inserts with increased modularity, membrane attachment became the main issue. After brainstorming ideas, I decided on 3 attatchment methods to test:

- Heat attachment

- Mechanical clamp

- Adhesive

First I began testing heat attachment methods. I used a hot plate to heat the membrane-frame interface. I tested a variety of heating times and found that the adhesion between the membrane and the frame was not sufficiently strong. Additionally, once the plastic reaches its glass transition temperature it becomes soft and experiences deformation. After this, I discarded the idea of heat attatchment.

Next, I designed a simple clamping mechanism. The bottom half of the insert is the female part, so i designed it in a way that the insert could be set into the bottom half and the top half would come down and press the membrane down into place. This design is shown in figure 3. This idea worked visually, however, it was very prone to water leakage. It is very important that the insert and membrane are watertight. Due to this, I no longer considered the mechanical clamping mechanism.

Last, I tested adhesives. The goal is for the inserts to be mass produced, so painting adhesive or epoxy onto each individual frame is not ideal. With mass production in mind, I turned towards spray adhesives. After testing spray adhesives I found that there was a tradeoff between adhesion strength and toxicity. Most of the strongest spray adhesives that I could find contained chemicals that would be harmful to cell cultures if there was any exposure. Additionally, the adhesive broke down after 2 days of being soaked in 70% ethanol. Ethanol is an possible alternative to autoclaving. Ideally parts will be able to withstand both ethanol and autoclaves so that the user has a choice of sterilization method that is most accessible. Due to the toxicity and poor chemical resistance, I did not choose to use an adhesive.

What is Currently Being Done?

After deciding that the previous 3 ideas were not going to work for mass-producible, chemically resistant, water-tight inserts, I had one final idea. I own a 3D printer, so i decided to try printing directly onto the membranes. The polycarbonate filament melts at temperatures that are too hot for the membranes (past its recommended temperature) however, this heat exposure is for a very short period of time. After many tests and printer settings adjustments, I had my first working prototypes. These prototypes are watertight and firmly attached. This method is also perfect for mass production. These prototypes are currently being tested.